A Texas candy company ditched artificial dyes before RFK Jr.’s tenure. It was a sticky process.

Natural dyes, which are derived from plants, produce, spices and minerals, have not been scrutinized as closely by researchers for their health impact or the potential for contamination, experts say. They are also not subject to the same stringent testing requirements as synthetic dyes. That has raised concerns among some food experts and consumer advocates about the unintended consequences of this shift — and whether it will actually make food safer and healthier.

“The important thing to remember with all colors, whether natural or synthetic, is that they are nothing more than marketing tools for food companies, to make foods look a certain way,” said Thomas Galligan, a toxicologist who works for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, an advocacy group. “At the end of the day, they aren’t strictly necessary. And so it’s important to weigh the risk against the benefit.”

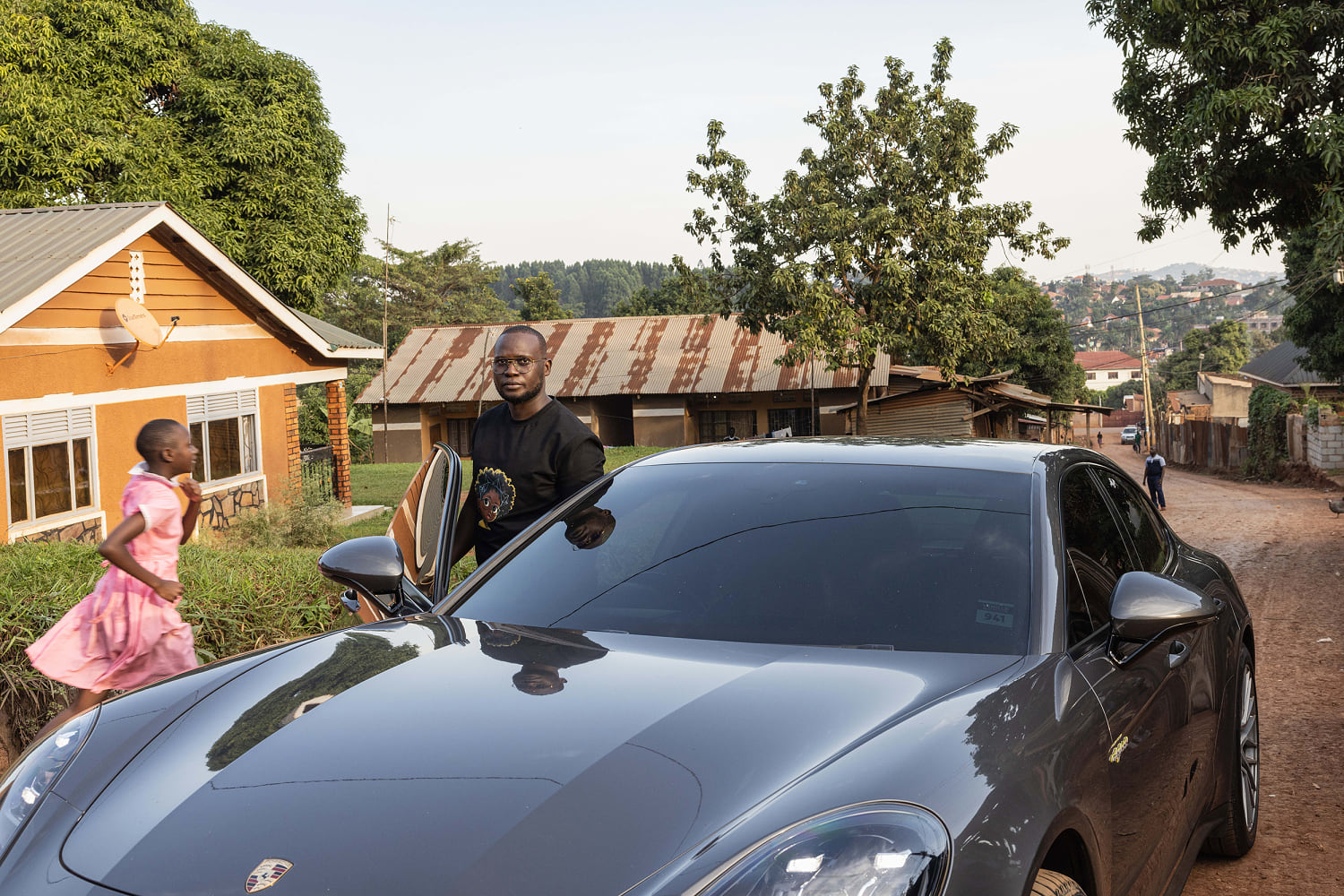

Eric Atkinson says he never thought synthetic dyes were unsafe. But when he read the ingredient lists for his company’s candies, which his family has been making since the Great Depression, they always struck him as out of place.

About 12 years ago, the company finally decided to make the leap. “We were so close to being all natural or all simple ingredients that we just went ahead and went there,” he said.

He knew how critical it was to get the color right for the Chick-O-Stick, the company’s most recognizable product. All the packaging for the candy mimics the color of the product, which Atkinson describes as “amber.”

“They say in the industry that taste is king, but color is queen,” he said. “The queen is very important.”

Working with food scientists for dye manufacturers, the company’s quality control team started testing mixtures of natural dyes to replicate the Chick-O-Stick’s signature hue. After years of testing, they came up with a combination of dyes derived from turmeric and vegetable juice — first trying beets before settling on radishes. But they later discovered that the color faded under LED light. This year, they switched again to annatto, a popular natural colorant made from the seeds of the achiote tree.

Another surprise was the funky smell that came from some of the natural colors. Atkinson recalls one particularly pungent dye made from red cabbages that smelled like rotting garbage, though the odor quickly dissipated when the candy reached the cooking step, where it’s heated to over 300 degrees.

That wasn’t the end of the challenges. Unlike synthetic dyes, which are easily produced in U.S. labs, the ingredients that form natural dyes are frequently imported. That introduces a host of complexities, including logistics, costs and product safety issues.

In March 2021, a container ship got stuck in the Suez Canal, making headlines worldwide. It also created a new headache for Atkinson: The ship was carrying the radishes used to create the Chick-O-Stick color at the time, sending the company scrambling for alternatives.

Even without such obstacles, it can be tough to find enough raw materials for natural dyes. It takes a considerable amount of seasonally grown produce — whether it’s radishes, red cabbages, blueberries or golden beets — to make dyes from fruits and vegetables. Carmine, a vibrant red colorant, is made from cactus-dwelling insects in Central and South America; 70,000 of those insects are required to create just over 2 pounds of dye.

Sourcing challenges often mean higher prices: One major dye manufacturer recently estimated that natural dyes cost about 10 times as much as the synthetic versions.

And then it can be a matter of convincing consumers. Though the color and appearance of the Chick-O-Stick had remained the same, not everyone was happy about the new formulation of a classic candy.

“We had a lot of pushback when we went to the natural colors,” said Atkinson. “Most of the feedback that we got was, ‘Quit changing our Chick-O-Stick.’”

Still, sales stayed steady, Atkinson said.