Trump’s ban stalls lifesaving treatment for Haitian children who need to travel for surgery

Leaders of an aid organization that has sent more than 100 Haitian children with serious cardiac conditions to the U.S. for heart surgery said President Donald Trump’s ban on travelers from 19 countries will stall or cancel lifesaving procedures for at least a dozen children or young adults.

The ban, which goes into effect Monday, has led to widespread uncertainty for many and drawn condemnation from international leaders. The proclamation issued Tuesday offered exceptions for those who are lawful permanent U.S. residents and those traveling to the U.S. for the World Cup and the Olympics, among other examples. No such mention was made for cases of medical necessity, such as those who are seeking treatment in the U.S. through the International Cardiac Alliance.

The International Cardiac Alliance’s total waitlist for Haitians, ranging from infants to young adults, totals at least 316 people who need heart surgery, said Executive Director Owen Robinson. Some are placed in hospitals in the Dominican Republic and occasionally the Cayman Islands. But there are currently five open surgical slots in the U.S.

“Some of them might be able to wait a few months, and others, if they don’t go now, they’re going to pass away very quickly,” Robinson said.

The president’s executive order adds that the secretary of state can issue exemptions for visas in cases that “serve a United States national interest.” It is unclear if clients of the International Cardiac Alliance with medical needs would fit into that description. Neither the White House nor the State Department responded to a request for comment on the matter.

“We do have kids die every week waiting because there’s not a lot of international slots for these kids,” Robinson said.

Some of the children in the program travel directly from their home country to the U.S., undergo surgery, and then return to Haiti. But for many Haitians, international travel requires multiple levels of logistical wrangling, Robinson said. Some patients and their parents who can secure surgeries in other countries must apply for a visa to the U.S., travel here, and then head to their eventual destination. The United States’ travel ban now throws a wrench in that process.

Fabienne Rene, 16, was diagnosed with rheumatic heart disease in February. Because of her condition, Fabienne, who lives in Port-au-Prince, cannot even attend school since she experiences shortness of breath, said her father, Fignole Rene. The “bad news” he received about the travel ban causing the postponement or potential cancellation of his daughter’s travel through the U.S. to the Dominican Republic is “really disturbing and breaking my heart,” he said.

“I was not waiting to hear something like that,” Rene, 53, said in Creole through a translator. “We know for sure that there is nowhere in Haiti we can have this possibility. The only option that we have was just waiting to have an open door from the Cardiac Alliance.”

He also said the news will be troubling for his family to hear and that they don’t know “where they will find another open door that can give her a chance.”

Robinson said the U.S. Embassy in Haiti recently informed him that it most likely wouldn’t be able to issue any visas due to the travel ban. In the past, the embassy has repeatedly issued visas for Haitian children to travel to the U.S. for care. The office of Rep. Becca Balint, D-Vt., has offered to reach out to the State Department to see if the children can receive exceptions, he added.

Dr. John Clark, a pediatric cardiologist at Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio who has worked with the ICA, said many children in impoverished countries like Haiti suffer from Fabienne’s condition because they are not seen by a doctor and treated for the common illness strep throat. Untreated, recurring strep infections can lead to rheumatic heart disease.

St. Damien Pediatric Hospital in Port-au-Prince received visiting pediatric surgical teams from 2015 to 2019, Robinson said. Now, dangerous conditions in Haiti prevent doctors from other countries from entering or providing care. Meanwhile, Haiti does not have enough doctors practicing there, and the loss of opportunities for a medical education in Haiti only perpetuates the problem, Clark said.

Clark participated in a surgical mission there in 2019, when visiting U.S. doctors were performing two heart surgeries per day, he said. A drastic rise in gang violence — including an attack on one of the hospital’s ambulances and a worker being stoned to death — ended most medical missions to Haiti.

Gang violence has only escalated since then, United Nations figures show, particularly after the assassination of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse in 2021. Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the world, and more than half of Haitians live below the poverty line. The country is also plagued with government corruption, gang violence and food insecurity, as well as vulnerability to natural disasters, including a devastating 2010 earthquake that killed at least 220,000 people. Lack of adequate health care also fuels diseases like cholera, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

“I hope things can calm down one day enough that we can get back there [to Haiti],” Clark said. “But right now, there’s no way for us to go back down.”

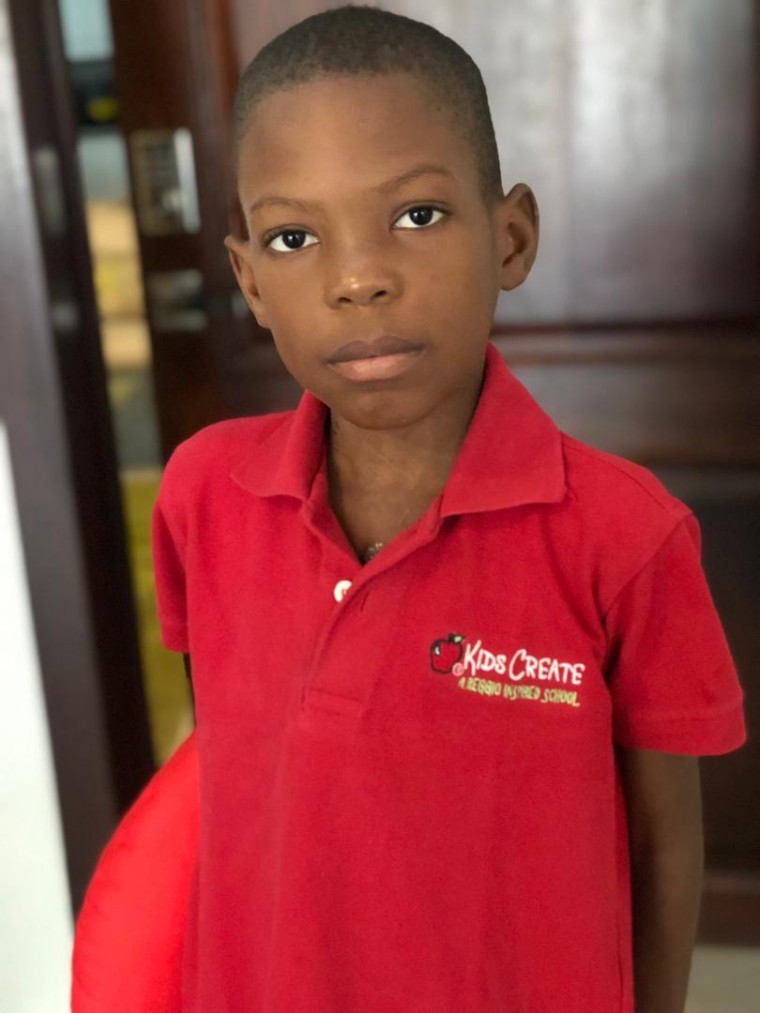

Andrice Boncoeur of Port-au-Prince received free open-heart surgery at CEDIMAT Cardiovascular Center in the Dominican Republic to repair a valve when he was 9 years old. That procedure, however, was only meant to be a temporary solution. Now, plans for Andrice, 16, to travel through the U.S. for more permanent surgery have been disrupted.

On Thursday, Andrice’s father, Andre Boncoeur, said he had not yet told his son about the travel ban preventing him from passing through the U.S. Boncoeur said he knows “something can change at any time.”

Still, children like Andrice do not have much time to wait. In April, Andrice was once again hospitalized for three days at Haiti’s Centre Hospitalier Eben-Ezer for heart failure. Boncoeur said his family has spent “everything that we had” and that their funds are “almost gone.” He said he hopes the situation will change so that his son, who aspires to become a pastor, “can have a chance to live his life as a normal kid.”

Clark, Robinson and the patient’s parents all agree it comes down to the Trump administration’s willingness to accommodate the sick children.

“These children are somebody’s child and somebody’s grandchild and they don’t have access to lifesaving care,” Clark said. “Is there any room for compassion?”